Becoming the Unaine

Swollen Shorelines

Less than a year after graduating high school, at nineteen years old, I chose to serve a mission for the church I grew up in. Once you submit your application, you are called by God’s chosen apostles to serve in a specific place. The details of where you’ll serve comes in a letter, and when my letter came, I opened it to read that I had been called to the Republic of Kiribati. I had never heard of the island nation before.

In 2013 as I descended the steps from the airplane the humidity was visible, the mosquitos were hungry, and I didn’t speak the language. Within my first few weeks on the island, I developed pneumonia that turned septic. The only medication the hospital had was an antibiotic that I was allergic to, and I nearly died.

Very quickly, I realized that survival is sharp. I felt the sharpnessness often. It came as the sunrays hit my pale skin and the pain of hunger in my stomach. The sharpness was lurking in the teeth of the wild dogs that roamed the island, and the cars that didn’t stop for anyone or anything when driving. It was in the unexpected rogue waves that hit hard when you turned your back to find the beach, and in my nails as they scratched mosquito bites on sunburnt skin- and then the sharpness would return when I would bathe, the well water stinging the open wounds becoming infected.

During this time of understanding sharpness, I became selfish. It didn’t make me a very good missionary or companion, since missionaries are never alone and always paired. This constant attachment to another human rivaled my own selfish need for survival, and yet, I relied on my companions like a newborn. I didn’t even know how to go to the bathroom without running water or porcelain toilets, or source food without supermarkets. My companions had an advantage I did not, they were daughters of the Pacific with heritage in Kiribati, Tonga, and Samoa. Survival became a group effort, and one that I contributed very little to.

It was also a group effort to learn the language. Always asking what a word meant, asking my companions to repeat it slower, moving the syllables around in my mouth like a too-hot soup. I listened to children mostly; their sentences were simpler and slower than the adults. I used my eyes to pick up on context clues and tried to piece together meaning. It took me about 9 gestational months to become conversational in the language of Kiribati. This was a pivotal moment for me as I relied a little less on my companions and had a little more independence.

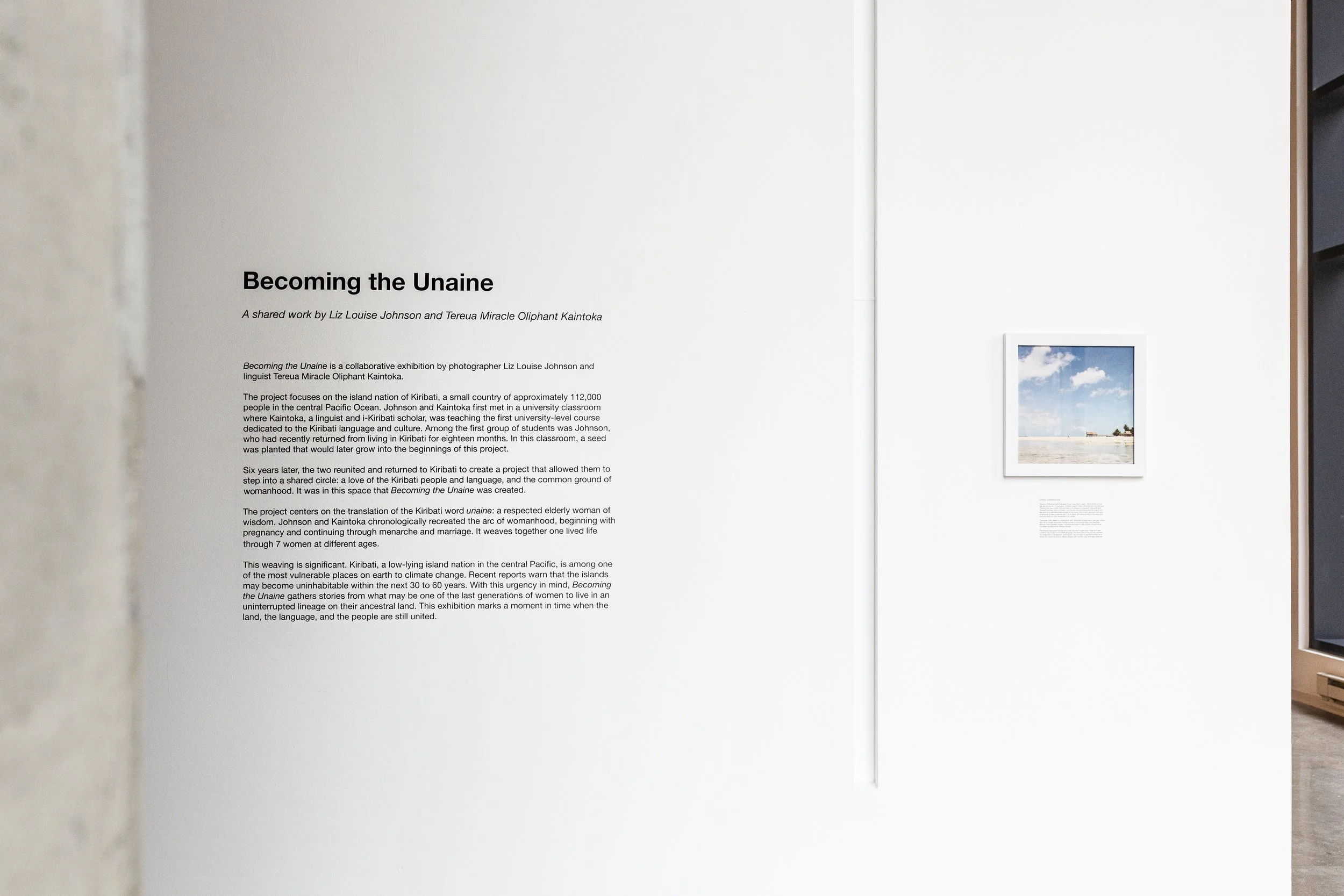

With access to the language it was then that I had access to the hearts of the people, and they had access to mine. The language uses the land as orientation instead of body words like left and right it is ocean-side lagoon-side. The language was my first lens into the emotional geography of the island as the word for ocean is one letter away from the word sister. “Time” and “Sun” are the same word, and to ask someone if they are married you would say, “do you have a balance for your canoe?”Land oriented language reflected the oneness felt between the experience of the body, and the experience of the land.

There is no word for “want” in Kiribati, It’s translated more along the lines of ‘close to or next to.’ I want to sleep | I kan ni matu | translated in Kiribati would be, I’m close to sleeping in the same way you would say something is close to the store, in a way of proximity; it has a “not there yet” feeling. The language is not a language built around lack or implications of lack but it is built around its proximity of relationship to the surrounding environment of closeness and community. My name in Kiribati is Eritabeta Tiaontin, and when I left in 2014, I promised myself I would never change.

And then for the past 12 years all I’ve done is change. I moved across the country, got married, left the church I grew up in, got divorced, started my master’s program, quit my full time job, moved to Alaska to work in the fishing industry, and reoriented myself after a season of deep grief that the divorce had brought and the unasked-for gift of freedom that singleness gave me. And yet throughout all this time, somewhere in me was the language and memory of Kiribati.

And so, after a decade I went back.

And like the first time I went, I did not go alone. I went with Tereua Miracle Oliphant Kaintoka, instead of my missionary companion, my research companion. We spent three weeks on the island photographing, interviewing, honoring, laughing, sweating and eating with the families in Kiribati. My language skills were rusty and I began to feel the familiar feeling of relying on my companion like I had 12 years earlier.

But this time I knew differently. I knew that our survival mattered. Both me and Tereua, so I put her first in a way I couldn't when I lived there as a 19 year old. I made sure she had first access to the shower, and made sure she was drinking water. I became ‘little sister’ to her, even though she is my elder of a couple months. Instead of fighting who I was, I embraced who I was. I am introverted, Tereua is extroverted. We somehow found a balance of our two cultures, two languages, two personalities, we found somewhere to meet in the middle exactly as we are.

The photos we took together were accompanied by interviews that were closer to conversations that Tereua recorded. And now, you become like 19 year old me, unable to understand the images or language. The interviews and captions for the photographs are not yet translated, but you hear the voice of Tereua in the background, her participation and part in the project.

This project is called Becoming the Unaine, and I think both Tereua and I could say it was also equally about who we both have become. The project is incomplete in the same ways our lives are incomplete, not yet finished, the same word for proximity in Kiribati.

In this way, this show and our story is not yet done.